Iluminan la historia genómica de las sociedades costeras de América del Sur

Iluminan la historia genómica de las sociedades costeras de América del Sur

Un equipo internacional co-liderado por el Instituto de Biología Evolutiva (IBE) ha recopilado el conjunto de datos genómicos más grande de Brasil para demostrar que las comunidades sambaqui de las costas del sur y sureste del país no representaban una población genéticamente homogénea.

El equipo de investigación ha analizado el genoma completo de 34 individuos de Brasil con una antigüedad de hasta 10.000 años. Estos incluyen datos genómicos de 'Luzio', un esqueleto encontrado en el sambaqui Capelinha y considerado la evidencia más antigua de presencia humana en el sureste de Brasil.

Publicado en Nature Ecology and Evolution, el estudio destaca el contraste entre las similitudes culturales de estas comunidades, descritas en el registro arqueológico, y sus diferentes trayectorias demográficas, posiblemente causadas por contactos regionales con grupos del interior.

Los sambaquis, también conocidos como "montículos de conchas", se establecieron hace aproximadamente entre 8.000 y 1.000 años a lo largo de más de 3.000 kilómetros en la costa este de Sudamérica. Según los registros arqueológicos, los constructores de sambaquis compartían claras similitudes culturales. Sin embargo, contrariamente a lo esperado, ahora un estudio co-liderado por el Instituto de Biología Evolutiva (IBE), un centro mixto del del CSIC y la Universidad Pompeu Fabra (UPF), ha revelado que estos grupos de personas mostraban diferencias genéticas significativas. La investigación, publicada en la revista "Nature Ecology and Evolution", atribuye estos hallazgos a las diferentes trayectorias demográficas de las poblaciones, posiblemente debidas a contactos regionales con grupos del interior. El equipo internacional, que ha contado con el Centro Senckenberg para la Evolución Humana y el Paleoambiente de la Universidad de Tübingen y la Universidad de São Paulo, ha recopilado el conjunto de datos genómicos más grande de Brasil, incluyendo a 'Luzio', la evidencia más antigua de presencia humana en el sureste del país.

En la costa atlántica de Brasil se encuentran montículos de conchas que alcanzan hasta varios cientos de metros de largo y ocasionalmente más de treinta metros de altura. "Estos vestigios culturales, conocidos como 'sambaquis', fueron construidos durante un período de 7,000 años. Consisten principalmente en conchas y otros residuos diarios que se fosilizaron con el tiempo. Los sambaquis fueron utilizados por antiguas poblaciones indígenas como viviendas, cementerios y demarcaciones territoriales. Son uno de los fenómenos arqueológicos más fascinantes de la América del Sur precolonial", explica el primer autor, Tiago Ferraz.

La investigadora principal del IBE Tábita Hünemeier, co-responsable del estudio, agrega: "Los sambaquis siempre fueron construidos de manera similar durante un largo período de tiempo en una amplia área. Las comunidades asociadas compartían similitudes culturales. Sus orígenes, historia demográfica y encuentros con cazadores-recolectores del Holoceno temprano del interior, junto con su rápida desaparición, han planteado varias preguntas que exploramos en este estudio".

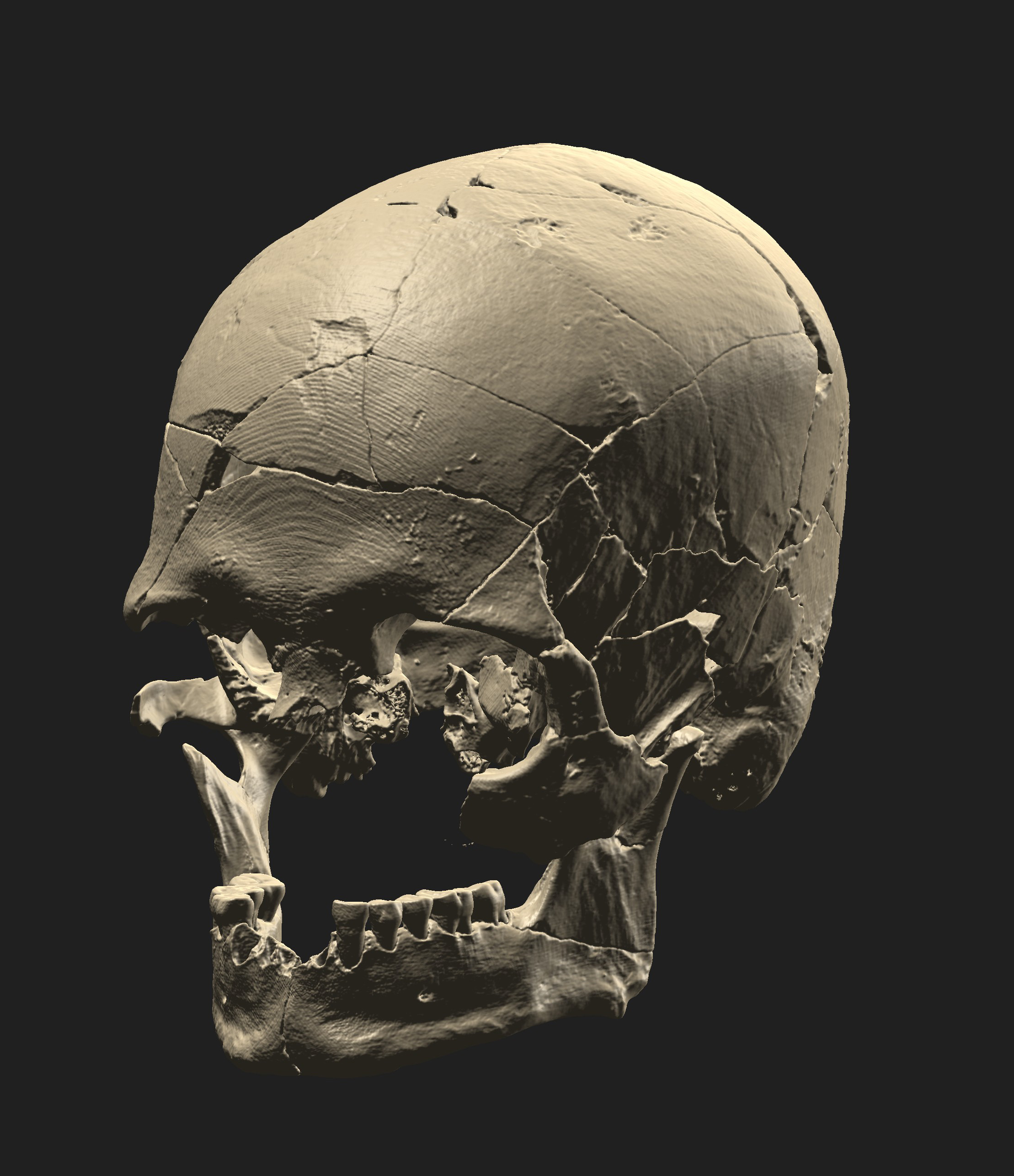

"Luzio”, un esqueleto encontrado en un sambaqui ribereño, es considerado la evidencia más antigua de presencia humana en el sureste de Brasil. Foto: André Strauss.

"Para aclarar aún más la historia poblacional de las sociedades indígenas en la costa este de América del Sur, generamos datos del genoma completo de 34 individuos de cuatro regiones diferentes de Brasil, con una antigüedad de hasta 10,000 años. Estos incluyen datos genómicos de 'Luzio', un esqueleto encontrado en un sambaqui fluvial llamado Capelinha. Es considerado la evidencia más antigua de presencia humana en el sureste de Brasil", explica André Strauss, del Museo de Arqueología y Etnología de la Universidad de São Paulo y co-responsable de la investigación.

En su estudio actual, los investigadores muestran que los cazadores-recolectores del Holoceno temprano son genéticamente distintos entre sí y de las poblaciones posteriores del este de América del Sur. Esto sugiere que no había relaciones directas con los grupos costeros posteriores. Los análisis del equipo también muestran que los grupos sambaqui contemporáneos de la costa sureste de Brasil, por un lado, y de la costa sur de Brasil, por otro, eran genéticamente heterogéneos.

Según el estudio, la intensificación de los contactos entre las poblaciones del interior y las costeras hace unos 2,200 años estuvo acompañada de un marcado declive en la construcción de montículos de conchas. Durante el mismo período, se produjeron importantes cambios ambientales. Los investigadores creen que todas estas influencias pueden haber llevado finalmente al fin de la arquitectura de los montículos de conchas.

Los análisis de los investigadores muestran que las comunidades sambaqui no eran una población genéticamente homogénea. Foto: Ximena Suárez Villagrán.

"En resumen, nuestros resultados muestran que las comunidades sambaqui en las costas del sur y sureste no representaban poblaciones genéticamente homogéneas. Ambas regiones mostraron diferentes trayectorias demográficas, posiblemente debido a la baja movilidad de los grupos costeros. Esto contrasta con las similitudes culturales descritas en el registro arqueológico. Necesitamos realizar más estudios regionales y a nivel micro para aprender más sobre la historia genómica de América del Sur", concluye el co-autor principal Cosimo Posth, del Centro Senckenberg para la Evolución Humana y el Paleoambiente de la Universidad de Tübingen.

Artículo referenciado: Tiago Ferraz, Tábita Hünemeier, André Strauss, Cosimo Posth et. al. (2023): Genomic history of coastal societies from eastern South America. Nature Ecology & Evolution. DOI: 10.1038/s41559-023-02114-9