Genetic adaptations help Amazonian populations resist Chagas infection

Science is full of SHEroes whose passion, work and creativity inspired Evolutionary Biologists of today.

As part of our commitment with society, the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE, CSIC-UPF) wants to give credit and visibility to the achievements of female scientists in evolution.

To that aim, we launched the campaign #WhoisyourSHEro to share stories of women who had an impact in our researchers' scientific career through our social media and website.

The campaign keeps on moving as more and more women in evolution are inspiring the IBE community.

You can join the conversation through social media under the hashtag #WhoisyourSHEro.

With the collaboration of the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology - Ministry of Science and Innovation.

|

Genetic adaptations help Amazonian populations resist Chagas infection

An international study co-led by the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE-CSIC-UPF) discovers a genetic variant that confers resistance to Chagas infection in Amazonian populations.

Chagas disease affects approximately 6 million people in Latin America alone and is one of the leading causes of death in this region. This infectious disease, also named American Trypanosomiasis, is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi (T.cruzi). However, despite being in contact with the parasite, Amazonian populations hardly suffer from Chagas infection. The investigation aimed to find out why.

The study, published yesterday in the journal Science Advances and co-led by the University of São Paulo and the IBE, in collaboration with the UPF Department of Medicine and Life Sciences (MELIS), has discovered a variant of the PPP3CA gene that reduces the risk of infection by the Chagas pathogen in Amazon populations.

It is known that tuberculosis and Chagas were found in the Amazon before the arrival of Europeans, but, to date, there have been no studies on the genetic adaptations of Amazonian populations to survive in this environment. For the first time, this research has shown that humans in the Americas underwent natural selection for this pathogen, in addition to other genetic adaptations.

Frequency map of the PPP3CA gene variant

To do this, the researchers analyzed the genomic data of 118 contemporary individuals from 19 different populations of the Amazon.

“We focused on finding evidence of positive natural selection related to tropical diseases in the Americas.” Tábita Hünemeier, Principal Investigator at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE-CSIC-UPF) who led the study, points out.

Through the analysis of the genomes, the study found a high-frequency variant of the PPP3CA gene in the inhabitants of Amazonia that could be responsible for this resistance. To verify its effectiveness, the research carried out functional studies in the laboratory with the collaboration of the Harvard Medical School.

Functional studies on the immunological action of the PPP3CA gene against the Chagas parasite

The PPP3CA gene codes for a key protein in the activation of immune cells, the innate immune response, and the internalization of the T.cruzi parasite in human cells. This study detected a variant of this gene in a very abundant way in Amazonian populations that is expressed in heart tissue and in immune cells.

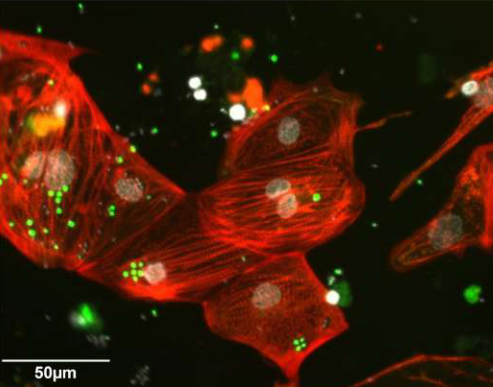

The study performed functional studies with heart cell tissue using stem cells, some of which contained the PPP3CA gene variant found in high frequency in Amazonian populations. The results showed that there is less internalization of the parasite in heart cells when they have the gene variant.

Heart cells during functional assays

“The presence of the PPP3CA gene variant could be the cause of milder disease or less infection in these populations.” Adds David Comas, Professor of Biology at the UPF, Principal Investigator at IBE (CSIC-UPF) and co-author of the research.

Positive natural selection in the Amazonian population due to a pathogen

Study results estimate that the natural selection for Chagas disease resistance began 7,500 years ago after the Amazonian population separated from the Andean and Pacific coast populations.

Supported by previous studies with 9,000-year-old samples, the research concludes that the epidemics would have positively selected the individuals with the greatest resistance to tropical diseases, such as Chagas disease, generating a unique resistance in this population.

Behavioral genetic adaptations to life in the jungle

Additionally, the study found genetic adaptations associated with behavioral traits such as "Novelty-seeking behaviors", a genetic trait that determines the search for new experiences. According to the study, this trait could have been crucial to the hunter-gatherer lifestyle of Amazonian populations in the past, as it enabled them to explore new territories and search for resources.

Cardiovascular and metabolic traits

The study also detected cardiovascular and metabolic traits that are consistent with the genetic predominance observed in previous research, since a 66% rate of obesity, diabetes, and coronary heart disease had already been detected in some Amazonian populations.

Reference article: Cainã M. Couto-Silva1, Kelly Nunes1, Gabriela Venturini, Marcos Araújo Castro e Silva, Lygia V. Pereira, David Comas, Alexandre Pereira, Tábita Hünemeier. Indigenous people from Amazon show genetic Q1 signatures of pathogen-driven selection. Science Advances.(2023) Vol 9, Issue 10. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abo0234