Sant Jordi's Books with IBE: "The Metamorphosis"

Sant Jordi's Books with IBE: "The Metamorphosis"

Franz Kafka's "The Metamorphosis," published in 1915, raises many unresolved questions about human identity, the value of the individual, and the concept of family. Furthermore, its author never revealed the identity of the "monster" the protagonist transforms into, and the clues scattered throughout the story ignite debate a century later.

We discuss this with José Luis Maestro, Principal Investigator of the Nutritional Signals in Insects Lab at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE), to uncover the secrets of one of the most controversial fiction books in the entomology world.

Would you recommend "The Metamorphosis" for "Sant Jordi"?

It's a very interesting narrative due to its grotesque nature: a man who suddenly wakes up transformed into an insect, as the first sentence of the story tells us. I find the beginning of the plot curious and surprising, and I'm eager to see how it unfolds.

For anyone interested in science, a book titled "The Metamorphosis" is bound to catch attention. The translation of the original title from German, "Die Verwandlung," is interesting. It refers to a nearly magical, irreversible change, reminiscent of Greek mythology. However, it also invokes thoughts of the natural history of certain animal groups, particularly insects, for whom this transformation is not magical but rather understood in terms of their biology and regulation.

Someone fond of insects would inevitably analyze the protagonist's description throughout the novel and even try to identify the insect species based on its morphology and behavior.

Could we try to identify which insect is being described based on the narrative?

Kafka likely had various insects in mind when describing the creature Gregor Samsa transforms into, perhaps even mixed, considering them somewhat similar. The first time the result of this transformation is described in the book is in the very first sentence, stating that Gregor has turned into an "Ungeziefer," which doesn't precisely mean insect but rather denotes a noxious, harmful animal.

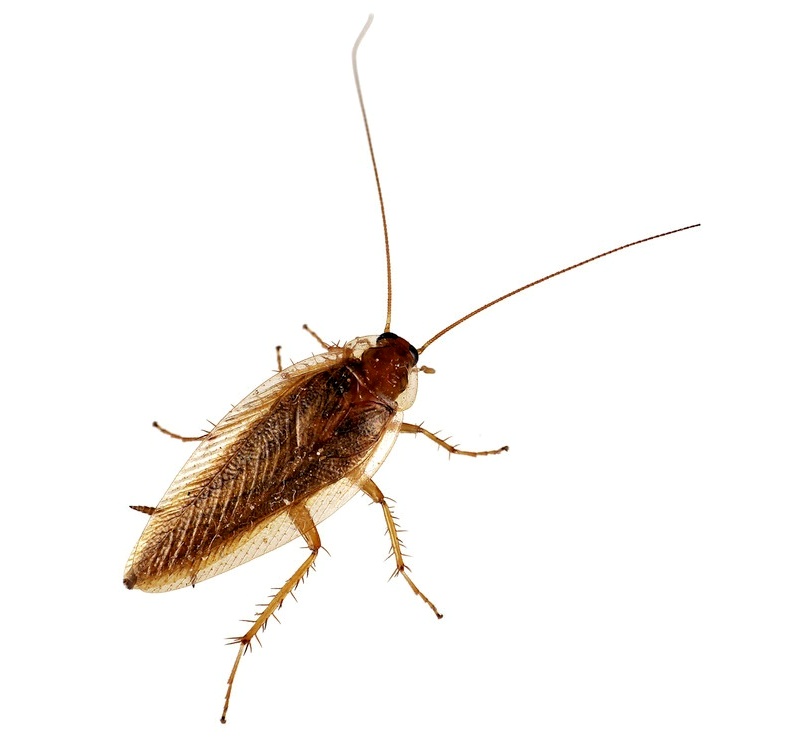

Moreover, there's a moment in the story where the maid refers to Gregor as a "Mistkäfer," or dung beetle. While some characteristics align with beetles, such as the arched back, others don't quite match, as his back isn't as hard as it would be if it were elytra. Indeed, the insect the author likely had in mind was the cockroach, as it's a common household pest and undoubtedly present in Prague, where he lived.

Additionally, some of the behaviors described are typical of cockroaches. Significantly, he mentions feeling very comfortable tightly squeezed under the sofa, as this is a characteristic of domestic cockroaches, which can easily fit into tight spaces and hide where they feel protected.

The narrative also states that Gregor prefers spoiled food over fresh. While this might seem like a cockroach trait because we find them scavenging in the garbage, in reality, they'll eat whatever they find, fresh or rotten, and they're in the trash because it's where they can easily find food. On the other hand, some other traits described are confusing.

It's mentioned that he has many legs, but it's never specified that he has six, as is characteristic of insects. It's also stated that when he moves, he leaves a trail of a sticky substance, which neither cockroaches nor any insect typically does.

Is there any characteristic of cockroaches that could have added depth to the story?

One characteristic common to all cockroaches and most insects, which the author could have explored more in the narrative, is the use of antennae, which are crucial sensory organs. Regarding domestic cockroaches, one of their traits is gregariousness; they like being in contact with each other. In Gregor Samsa's case, this gregariousness would have likely driven him to leave his room more often and seek the company of his family members.

Initially, Samsa and his family seem unfamiliar with cockroaches, as they treat him as a "monster." What would a cockroach expert have done in his place? What would be the "survival protocol" if we ever transformed into cockroaches?

That depends on the type of cockroach we transform into. Wild cockroaches each have their own way of life. If we were to transform into domestic cockroaches like the German cockroach, Blattella germanica, which is the species we primarily study in our group, we would seek warmth, humidity, organic remains to eat, and the company of other cockroaches. With these conditions, we would be quite comfortable.

What do we know now about cockroaches that we didn't a century ago, when this book was published?

At that time, much was known about the distribution, anatomy, and even embryonic development of the most common species.

However, the number of known species has multiplied at least fourfold since then. Currently, there are approximately 4600 described cockroach species, of which only about thirty are domiciliary and can live with us, and of these, only three or four species are considered significant pests. The rest are wild species, many of them with spectacular forms and colors due to their beauty.

Interestingly, around the same time Kafka was writing "The Metamorphosis," Thomas Hunt Morgan was initiating the Fly Room at Columbia University, which marked the beginning of genetic studies in insects and subsequently enabled their use as models to study cellular, biochemical, metabolic, evolutionary processes, etc., not only in Drosophila melanogaster but also in other insect models that have emerged since then, including cockroaches.

What questions remain unknown about these insects?

Today, there are many interesting evolutionary questions to answer to understand adaptation and biodiversity maintenance, such as:

- The domestication of domiciliary species, which seems to have involved the acquisition of a large number of genes for resistance to toxins and insecticides.

- Evolution towards viviparity: within the group of cockroaches, there are species ranging from strict oviparous to viviparous, with various intermediate situations. This process has involved different hormonal and signaling adaptations.

- Adaptation to cave life: comparing closely related cave-dwelling and non-cave-dwelling species.

- The emergence of eusociality in termites: termites are essentially social cockroaches. The development of complex social organization with different castes occurred independently in this group, as it did in hymenopterans (bees, ants, and wasps), making it an evolutionary mystery.

What are you currently researching in the Insect Nutritional Signals group at IBE?

We're wrapping up a project that analyzes another evolutionary trait unique to cockroaches. This project examines the insulin receptor pathway, which, like in humans, is a crucial signaling pathway in insects.

In general, insects have two insulin receptors due to a gene duplication that occurred in the ancestor of all winged insects. However, cockroaches have three because a second gene duplication occurred later in the cockroach lineage and related groups like mantises and stick insects.

Both duplications are ancient, and the fact that they have persisted for so long indicates that the resulting genes must provide some functional advantage. So, in our project, using the German cockroach Blattella germanica as a model, we aim to study the functions of each of the three genes and how they relate to each other to identify the evolutionary mechanism by which the three copies have been maintained.

The results so far show that there hasn't been a functional specialization of any of the three receptors; instead, they act cooperatively. Thus, the joint function of all three genes stabilizes the system to effectively regulate such an important signaling pathway as the insulin receptor.